A brief history | Factsheet | Articles | Live blogs | Videos | Contact

A brief history | Factsheet | Articles | Live blogs | Videos | Contact

Sometime in the mid 1980s an annual jumble sale started in what would become known as Manchester's gay village. The aim was to raise money to help with HIV & AIDS and have a little fun. In 1991 the event was called "The Carnival of Fun Weekend."

Sometime in the mid 1980s an annual jumble sale started in what would become known as Manchester's gay village. The aim was to raise money to help with HIV & AIDS and have a little fun. In 1991 the event was called "The Carnival of Fun Weekend."

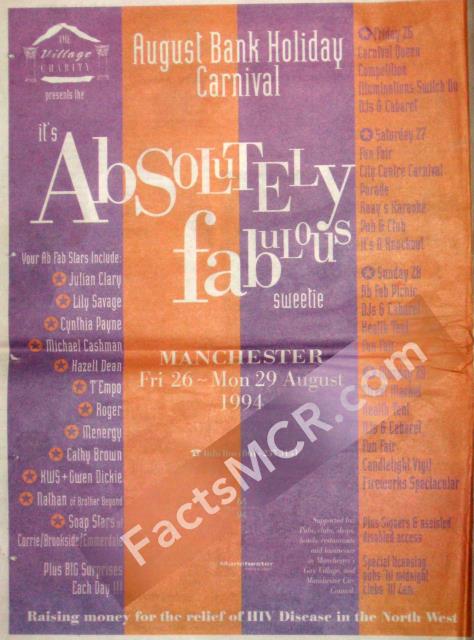

We believe in 1992 or 93 it was called "Tickled Pink" and in 1994 the "AbFab August Bank Holiday Carnival". After that the weekend was known as Manchester Mardi Gras and, by the second half of the 1990s, it had turned into a huge free event.

See the article in our 2022 factsheet (PDF) to understand why the August weekend was neither a "pride" nor a protest, despite endless modern day claims that it was these things.

By then the gay village had grown to include dozens of bars and clubs and other businesses. Historic buildings had been converted into private housing. During Mardi Gras stages were put up in the public park and on the car-parks.

In 1998 wristbands were introduced for entry at the doors of bars and clubs. The following year, 1999, Mardi Gras was run from the town hall, headed up by councillors. The entire gay village area was fenced off for the first time with a promise that 50% of the profit from the "pledgeband" would go to good causes.

But, despite income of £384,000 and 45,000 bands sold, things ended in scandal when it was revealed there was no money left after costs. The event reverted to being free for three years — as GayFest in 2000 and 2001, organised by Julia Grant and her team, and then as Mardi Gras in 2002.

In November 2002 the organisers, police, City Council and gay charities attended a meeting. They were told the streets could be closed using one of two methods but neither allowed a charge to be made to enter. Campaigners discovered minutes of this meeting in the Library Archives in 2016.

In August 2003 the streets were again fenced off and closed to pedestrians. A paid wristband or resident's pass was required to enter during Manchester Europride, as it was known that year. It isn't clear why the City Council and others did this when they had been told they couldn't, the previous November. Nor is it clear why Greater Manchester Police allowed this unlawful closure of pavements and charging to go ahead.

From 2003-2006 the wristband scheme ("Operation Fundraiser") was run by the Lesbian & Gay Foundation (now known as the LGBT Foundation) and George House Trust. Both profited from it and both had been at the November 2002 meeting.

In 2007 and 2008 our undercover filming confirmed that members of the public were being told they must buy a wristband to attend the Monday HIV/AIDS Vigil. An event that supposedly was free entry for all. We showed how those without bands, some who had lost relatives to AIDS, were made to queue on the street outside the fenced area for a long period. Leaving them feeling disrespected.

In spring 2011 we launched our campaign Facts About Manchester Pride, founded by Wynnie and Geoff. We had concerns about exclusion, fundraising and the event not being put out to tender. There hadn't been a public meeting for more than a decade. We held one in summer of that year. Our Facebook group had more than 1,000 members. We organised protests and received considerable media coverage — in the mainstream and gay press.

A resident sent us a copy of the letter Manchester Pride sent out in 2011, claiming to have the power to "grant" or deny access to their homes during the four-day event.

In 2010, Mr W, a gay man who lived in the gay village, decided to hold the reception for his civil partnership ceremony at his own home during Manchester Pride weekend. Arrangements were made with Pride but, on the day, the organisation's security guards refused to let his family and friends walk to his front door and eventually they had to leave.

This led to Mr W selling his home and moving away. It's an example of the impact the bossy, controlling, but disorganised individuals at Manchester Pride had. While the media didn't report.

In 2013 our campaigners were tipped off that in previous years several bars had demanded that customers should be able to walk to their premises without buying a wristband and this had been facilitated. In an email reply to us the Head of Events at Manchester City Council admitted that the public had a right to walk across the event site. But it was too late for us to do anything about that year's Pride. By this time, people who couldn't afford a wristband had been locked out from the gay village every Pride weekend for more than a decade. Prevented from having even a walk around.

After more than two years of running the large and lively Facebook group we decided to scale back that and focus our time on publishing.

With Julia Grant we drew up a business plan for a replacement event. A major bank was willing to sponsor it and funds raised would pay for a new community centre. However it seems not enough of the Gay Village businesses supported the plan.

We'd always been willing to engage with Manchester Pride. We'd met with the CEO and other representatives many times. In late 2013 we were promised there would be change and that one controversial person would stand down. But it turned out to be a red herring and not for the first time. We decided that discussions were pointless — just a strategy to manipulate and waste our time.

Manchester Pride made a loss in 2013 but this was hidden from the public and the CEO stood down. Pride used money from the bank account to create a charity amount of £34,000 it could announce. It became clear that Manchester Pride sometimes held back or topped up money. It could be said to manipulate public opinion and fend off criticism. So the announced amount for causes wasn't necessarily a reflection of the actual fundraising in a particular year.

We were tipped off about the loss and, at the end of 2013 with the help of a Liberal Democrat councillor, we asked one of the scrutiny committees at Manchester City Council to look at Pride. Strings were pulled and the investigation was moved from a committee that had a LibDem chair, to one that was chaired by a Labour councillor.

In early 2014, the scrutiny committee gave Manchester Pride a glowing report. The committee's minutes even claimed, falsely, that Pride was the largest event of its kind in the world (the highest number of wristbands sold was 51,000 in 1998).

We had tried. But it was clear there was no point engaging with a City Council that would do this. No doubt the virtue-signalling councillors felt smug. In reality it was one more example of how the people who controlled this event and charity kept digging a deeper hole for themselves.

We decided to press the "nuclear" button and involve the Department For Transport (DFT) to dismantle the exploitative business model.

Before the event in 2014 the DFT spelt out the situation in letters to us. It made clear that pedestrians couldn't be stopped from walking to homes and business premises when no other access route existed. There was widespread publicity about this: on BBC radio, in the Manchester Evening News and gay media outlets. However during the event, campaigners were illegally blocked at the gates by Pride's security guards, assisted by officers from Greater Manchester Police.

Before the event in 2014 the DFT spelt out the situation in letters to us. It made clear that pedestrians couldn't be stopped from walking to homes and business premises when no other access route existed. There was widespread publicity about this: on BBC radio, in the Manchester Evening News and gay media outlets. However during the event, campaigners were illegally blocked at the gates by Pride's security guards, assisted by officers from Greater Manchester Police.

A gay man who had a wristband and was on a public pavement was assaulted by Manchester Pride's security guards. They dragged him out of the fenced area while police officers watched and did nothing. The incident was recorded on video. During the weeked it became clear that some bars and clubs would allow people in without a wristband.

In December 2014 representatives of Greater Manchester Police (GMP) and members of its LGBT staff group "Police With Pride" showed clear bias at a Manchester Pride "Listening Group." They described the right of way campaign as "hype" and campaigners as people "we" had to "deal with." The chair of the Pride trustees told the meeting "having GMP in the Parade is a large political statement in itself."

The CEO of Pride misled the meeting about street closures, despite the DFT having sent copies of correspondence to Manchester Pride more than three months earlier.

In April 2015 the Local Government Ombudsman ruled that Manchester City Council had acted "unlawfully" when it mentioned wristbands in a road traffic order. This being the mechanism that had been used to restrict pedestrians from the pavements and force permits on residents and their guests.

A news blackout began, across all mainstream and gay media. In August 2015 the Manchester Evening News told its readers that a wristband was required for the event "as usual." A lie. In this letter to us in December 2020 the BBC explains that not reporting the story is an editorial judgement that best serves you the BBC viewer...

Because of this lack of publicity, people continued to be misled in a subtle way and many paid unnecessarily. However we got the word out to more people each year through our annual factsheets, this website (with 45,000 unique visitors a year) and by word of mouth.

Before the event in 2015, the chair of Pride's Community Collective, a bar manager, tried to organise a boycott of takeaway businesses within the fenced area, because none of them had "donated" to Manchester Pride. Not only were law-abiding businesses seeing customers who didn't buy a wristband blocked from reaching their premises, but now they faced a boycott by those who did buy a band.

The police began to do the right thing from 2015 onwards. But in letters Greater Manchester Police refused to investigate what had taken place since 2003. In 2015 a former Police Federation expert told the BBC that the professional standards department of Greater Manchester Police was "corrupt." In 2020 GMP was placed into special measures by the government.

In late 2017 Manchester City Council announced that the NCP car-park where much of Manchester Pride took place would be redeveloped. Was this a face-saving exercise? We don't know. No development has taken place.

August 2018 saw the last Manchester Pride on the car-park area.

Because Manchester Pride closes roads to vehicles for more than three days, each year the City Council has to apply to the Secretary of State for permission. In 2018 the Council didn't submit the Road Traffic Order until the day Pride began and it was never approved.

This means no valid Traffic Order was in place for some or all of the four-day event and roads were closed to vehicles unlawfully. An "unprecedented" situation for an event on this scale, according to one expert we talked with.

In 2019 the Gay Village Party took place with the streets open but a wristband required for private areas and venues. We recorded a worrying number of incidents of people being misled and charged, in our live blog.

The main Pride event moved to Mayfield Station. Some people believe tragedy was narrowly avoided due to overcrowding and lack of water.

A journalist from The Independent reported that, despite paying £80 for a ticket for the "shambolic" Mayfield event, she had to urinate in a plastic cup due to lack of toilets. "Unenjoyable at best and downright dangerous at worst," she concluded. Manchester City Council promised an investigation and up popped Councillor Pat Karney who was Chair of the fundraising failure back in 1999...

In July 2021, in response to a Freedom of Information (FOI) request, the City Council told us it had no minutes or paperwork for any of the meetings concerning what had happened at Mayfield, because the meetings had taken place at Manchester Pride.

Manchester Pride was cancelled in 2020 due to the Covid virus and the organisers received a government handout. Questions began to be asked about the fundraising.

Back in year ending 31 December 2018 Manchester Pride had income of £2.34 million and after everything had been spent there was a reserve in the bank of £263,019. Staff costs for the year were £191,033.

We started this event in the 1980s to raise funds to help with HIV and AIDS. It wasn't a "pride" and that word didn't appear in the name until 2003 when Marketing Manchester (the tourist board) renamed it without asking the community.

Back in 2013 we began to sense that the people behind the event were trying to manipulate so that Manchester Pride itself was the "good cause."

In the era of Covid, was the "good cause" keeping the staff in jobs? In 2018 we reported that the staff of Manchester Pride had enjoyed an earnings increase of 56.27% per head in the four-year period since 2014 (see our 2018 factsheet).

The late Julia Grant said that Manchester gets the pride it deserves. In the end each of us has to decide whether this organisation and event in its current form is something we approve of and want to support with our money.

Certainly it is an inefficient way to fund needy charity organisations, with just a few percent of the income going to them even in a good year. It is far more effective to give money to good causes directly.

Our 2022 Factsheet (PDF) about Manchester Pride is available (there won't be a new factsheet for 2023). Read about your right to access the Gay Village without buying a wristband, history & opinion .

Our 2022 Factsheet (PDF) about Manchester Pride is available (there won't be a new factsheet for 2023). Read about your right to access the Gay Village without buying a wristband, history & opinion .

Download the PDF version.

And here it is as two images (handy for sharing on social media): page 1 | page 2

Our factsheet from 2021 is still well-worth a look. It has four pages of facts, gossip and fun. Download it as a PDF here. See our factsheets page for other years.

The ruling by the Local Government Ombudsman in April 2015 (PDF). The Ombudsman decided that Manchester City Council had exceeded its powers by mentioning wristbands in a traffic order and that it was unlawful to restrict access to premises (businesses and homes).

Minutes of a meeting at Marketing Manchester in November 2002. These show that those present were told they couldn't charge people to enter public streets. However some of them went ahead and did so from 2003 onwards for a decade.

At the meeting were: Manchester City Council, GHT, the LGF (now known as the LGBT Foundation), Marketing Manchester, the organisers of Europride 2003. The advice seems to have come from the police. Yet the police apparently then turned a blind eye...

This document was unearthed at the Library Archives quite recently by a FactsMCR campaigner.

Since the ruling by the Local Government Ombudsman in 2015 the media — both LGBT and mainstream — have stayed silent about the decade-long wristband fiddle and your rights. So some people continue to pay unnecessarily.

All your favourites know: GayStarNews, Pink News, Manchester Evening News, The Guardian, BBC and many more. In a letter to us, the BBC defended its journalist right not to report this. The same BBC that championed consumer rights at one time now prefers to cosy up to the civil-rights-infringing Manchester Pride, as a "sponsor" (the BBC says it doesn't give money).

These organisations don't need to lie. They simply ignore an issue completely. Or, they report some of the facts; perhaps popping in just one or two bits they don't like, to add a fake impression of balance. That's how they manipulate opinion in the direction they think it should go.

The veteran ITV reporter John Pilger says that "not reporting" is the most powerful form of censorship.

What else aren't they telling us?

© Copyright 2025. All Rights Reserved. | Cookies, Privacy & Data